MIT 6.172 Performance Engineering

Notes

- Rule of Thumb: Parallelize outer loops instead of inner loops.

- Floating points aren’t associative this restricts the compilers from changing the order of evaluation which might potentially improve the speed.

-ffast-mathflag allows the compilers to reorder which will result in improved performance but might result in unexpected results.

// This is performance engineering

for {

think();

code();

test();

}

Bentley’s Rules for Optimizing Work

- Given by Jon Bentley (mostly). The rules have been modernised though.

- Work: The work of a program (on a given input) is the sum of all the operations executed by the program.

- Must be noted that reducing work might not always reduce the running time owing to the underlying hardware complexity.

- There are 4 major categories for Bentley’s rules

- Data Structures

Packing and Encoding: Idea is to store as much data as possible in one machine word which can be achieved by achieved by encoding the data in a certain way such that it uses lesser bits (imagine JSON vs protobufs).

For example:

// This struct encodes a date in just 22 bits // but would have significantly more space had // this been stored as a string. // // Interestingly, because of padding at the end, // the actual size would still be 32 bits // (10 bits of padding) typedef struct { int year: 13; int month: 4; int day: 5; } date_t;While packing/encoding is an important optimization, it needs to be ensured that decoding doesn’t becomes very difficult.

Should be ideally be used when data needs to be moved around more frequently then it is to be decoded.

Augmentation: Augment the data structures such that we preserve informations which might help us later in reducing some work.

For example: In a linked list if we offer a peek last then it is worth storing a tail pointer in the list which helps us avoiding iterating to the end of list everytime a peek is requested.

Precomputation: Precompute as much as possible, increases compile time but can significantly improve runtime performance.

For example:

nCrcalculations would require a pascal’s triangle. A partial pascal’s triangle can be precomputed and stored during compile time.CAUTION: Too much precomputed data can and will affect instruction cache.

Caching: Store results which were accessed recently.

🤔: What if fetching cache is costlier than computing again?

Sparsity: Don’t store zeroes, don’t compute them if not needed. For example, we know

A * 0 = 0andA + 0 = 0.More concrete example, use Compressed Sparse Row (CSR) instead of a

n x nmatrix when it is a sparse matrix.

- Logic

Constant folding & propagation

Example:

const RADIUS = 12 const PI = 3.14 // Go will "fold" this, that is, AREA value will already be there // in the assembly - Yeah, I verified const AREA = PI * RADIUS * RADIUSCommon Subexpression Elimination: Identify repeated computations and eliminate them by doing them once and reusing the result. Kinda like caching except that in caching we store the result somewhere else (in a cache dedicated variable) while CSE eliminates the common re-evaluation only which means that the result is already being used somewhere else in the expression (no dedicated cache variable).

For example:

// ... a = b + c b = a - d c = b + c d = a - d // ... // The above can be rewritten as a = b + c b = a - d c = b + c // can't be `c = a` d = bAlgebraic Identities: Simple idea, modify the identities such that they rely on cheaper (from hardware perspective) mathematical operations. For example,

sqrtis a very expensive operations and if can be avoided, it should be avoided.Short Circuiting: Use conditionals for early exists.

🤔: I wonder if it would be worth risking branch misprediction if the function bodies aren’t expensive.

Ordering tests (conditionals): The idea is that the tests which is most likely to be successful (or fail) should be done first.

For example:

func is_whitespace(c: byte) bool { return c == '\r' || c == '\t' || c == ' ' || c == '\n' } // the above can be replaced with, in a document, it is far more // likely to hit a <space> than it is to hit a carriage return, so // test for that first, saves us 3 additional checks func is_whitespace(c: byte) bool { return c == ' ' || c == '\n' || c == '\t' || c == '\r' }Create a fast path: The idea is that if tests (conditionals) are expensive to compute then use a cheaper approximate test and only if that test fails, jump to the more expensive computation.

Combine tests: The idea is that instead of using nested

if, use bit magic (or any other technique) which can make the tests more plane.Confused? Check the video.

- Loops

Hoisting: Avoid recomputation of loop in-variant code each time through the body of a loop.

Sentinels: Use sentinels to simplify boundary checks and use them for early exits wherever possible.

Loop Unrolling: There are 2 types: (i) Full loop unrolling (ii) Parial loop unrolling. (ii) is more commoon due to being more compiler optimization friendly.

If the unrolled loop is huge then just like precomputation, it will affect instruction cache.

Loop Fusion/Jamming: Basically merge multiple loops together. There are 2 primary advantages:

- Lesser loop control overhead

- The data being fetched in one loop might be fetched again in another, if the loops are merged then fetching can be done just once.

Eliminating wasted iterations: Do not iterate if it is not required. If a cheaper test can give us early exit, use it, it will save us the loop control overhead.

- Functions

Inlining: Obviously, just inline the damn function. Never too much though, again instruction cache issue will popup.

Tail recursion elimination: If and whenever possible, eliminate tail recursion. Function calls have their own overhead.

Coarsening recursion: The idea here is to have a more coarse base case.

For example:

func quicksort(arr []int, len int) { if len > 0 { // do stuff recursively } } // Instead of having the above, we can func quicksort(arr []int, len int) { if len < THRESHOLD { insertion_sort(arr, len) return } // do stuff recursively }

- Data Structures

Bit Hacks

Unsigned Integer representation: \(x = \sum_{k = 0}^{w - 1} x_k 2^k\) where

xis awbit word.Signed Integer representation (2’s complement): \(x = \left(\sum_{k = 0}^{w - 2} x_k 2^k \right) - x_{w - 1} 2^{w - 1}\) where

xis awbit word.- Left most bit is the sign bit.

0b000...000is0while0b111...111is-1.x + ~x = -1(if you woud think hard about it, you would realize that adding each individual bit will always look like1 + 0, hence it will always be0b111...111which is-1). This also yields that-x = ~x + 1.

Some of the bit hacks can be extended to vectors as well.

Set

kthbit to1:y = x | (1 << k)Set

kthbit to0:y = x & ~(1 << k)Toggle

kthbit:y = x ^ (1 << k)Extract a bitfield from a word

x:(x & mask) >> shift.🤔: How do I effienciently create the mask though? FWIW in C, it will generate assembly for me if I use bitfields in structs.

Set a bitfield in a word

xto valuey:x = (x & ~mask) | ((y << shift) & mask). Here, the& maskis done to ensure that any garbage value inydoes not pollutex.Swap integers

xandy:x = x ^ y; y = x ^ y; x = x ^ y;(Remember,x ^ x = 0,x ^ 0 = xand XOR is associative).This will perform poorly than a simple temp variable swap because this won’t have any instruction-level parallelism (ILP).

Branchless unsigned integer minimum

r:r = y ^ ((x ^ y) & -(x < y))🤯.Might not work as it is in golang, will require either a conversion or unsafe casting.

__restrictor in C99restrictkeyword tells the compiler that there are no aliases to a pointer which allows the compiler to do more optimizations.A branch is predictable if it returns the same value most of the time. See a nice branchless 2way merge here.

It is noted that on modern machines a branchless 2 way merge sort would be slower than the branched version because compiler is smarter and figures out better optimization (like using

CMOVinstruction, etc.To compute

(x + y) % nsuch that0 <= x < nand0 <= y < n, we can usez = x + y; r = z - (n & -(z >= n));.Round up to a power of 2. The solution is pretty intuitive.

uint64_t n; // ... --n; n |= n >> 1; n |= n >> 2; n |= n >> 4; n |= n >> 8; n |= n >> 16; n |= n >> 32; ++n;Compute the mask of least significant bit of a word

x.mask = x & ~(x - 1) = x & (-x).To compute

lg(x)wherelg(x)isln(x)/ln(2)andxis a power of 2, we need to know de Bruijn sequence.

de Bruijn Sequence

A de Bruijn sequence \(s\) of length \(2^k\) is a cycling 0-1 sequence such that each of the \(2^k\) 0-1 strings of length \(k\) occurs exactly once as a substring of \(s\).

For example, deBruijn sequence for k = 3 will be 00011101.

It has many use cases including calculating the power of 2.

The basic idea behind it is that we have, a de bruijn sequence for k and a table which maps the substrings to their location in the sequence then we can simply:

// because x is power of 2, it is eq to shifting

uint64_t shifted_sequence = sequence * x;

// lookup in the table

int pow = table[shifted_sequence >> seq_len];

Now a days there are hardware instructions that will do this automatically

N Queens Problem

The solution is good old backtracking but board representation should we use?

n * nbytes (2d array of bytes)?n * nbits (2d array of bits)?nbytes (we any way just need to store the position of queen in the row at a time)?

A more compact representation is using 3 bitvectors of size n, 2n - 1 and 2n - 1.

Population Count Problem

Count the number of 1 bits in a word x.

for (r = 0; x != 0; r++)

// this is eliminating least significant 1

x &= x - 1;

The issue with above solution is that it is really efficient if there are less number of bits set to 1 however the performance degrades as the number of 1s increases.

Another solution is to store all the 1s count for each 8 bit word (256 total) in a lookup table and iterate over words in a batch size of 8.

static const int count[256] = {...};

int r;

for (r = 0; x != 0; x >>= 8)

r += count[x & 0xFF];

The performance of above operation is primarly constrained by the memory access speed.

There is another even more efficient (and crazy and obfsucated) solution to this problem

// Create masks

M5 = ~((-1) << 32); // 0^32 1^32

M4 = M5 ^ (M5 << 16); // (0^16 1^16)^2

M3 = M4 ^ (M4 << 8); // (0^8 1^8)^4

M2 = M3 ^ (M3 << 4); // (0^4 1^4)^8

M1 = M2 ^ (M2 << 2); // (0^2 1^2)^16

M0 = M1 ^ (M1 << 0); // (01)^32

// Compute popcount

x = ((x >> 1) & M0) + (x & M0);

x = ((x >> 2) & M1) + (x & M1);

x = ((x >> 4) + x) & M2;

x = ((x >> 8) + x) & M3;

x = ((x >> 16) + x) & M4;

x = ((x >> 32) + x) & M5;

The above is a brainfuck but is extremely performant. No need to do this though, most modern hardware have popcount instructions now.

Assembly Language and Computer Architecture

Four stages of compilation

- Preprocess (can be invoked manually by

clang -E) -> Produces preprocessed source - Compile (can be invoked manually by

clang -S) -> Produces assembly - Assemble (can be invoked manually by

clang -c) -> Produces object file - Link (can be invoked manually by

ld) -> Produces final binary

objdumpcan be used to disassemble if the program was compiled with-g(preserve debug info).

Why look at assembly?

- Compiler is a software might have bug.

- Edit assembly by hand if something isn’t possible in the higher level language.

- Reveals what the compiler did and did not do.

- Reverse engineering.

“If you really wanna understand something, you wanna understand it to the level what’s necessary and one level below that.” - Charles Leiserson

Instruction Set Architecture

Specifies the syntax and semantics of assembly. There are 4 important concepts in ISA:

- Registers

- Instructions

- Data Types

- Memory addressing modes

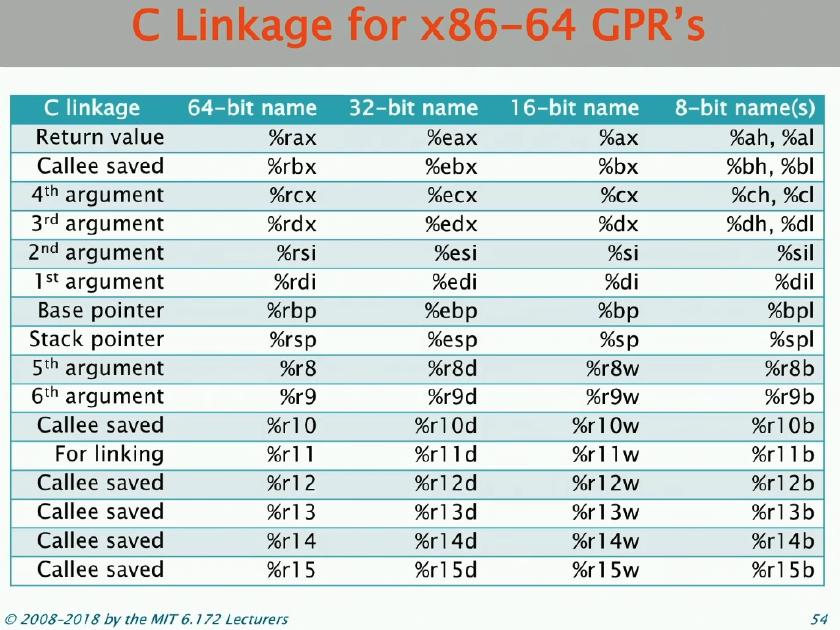

Registers

Some important x86 registers

- General Purpose Registers (16)

- Flags register - store the status of ops, etc

- Instruction Pointer Register - Mostly assembly execution is linear so this keeps track of the current line

- AVX, SSE registers for SIMD operations

x86-64 did not start as x86-64 rather the word size was 16 bits initially, this is evident from the register names today.

Layout

-------------------------------------------------------

%rax

-------------------------------------------------------

| %eax

-------------------------------------------------------

| | %ax

-------------------------------------------------------

| | %ah | %al

-------------------------------------------------------

B7 | B6 | B5 | B4 | B3 | B2 | B1 | B0

-------------------------------------------------------

Only %rax, %rbx, %rcx and %rdx have a seperate register name to access B1.

raxwas the accumulator register on which you principally did arithmeticrbxwas the base register from which you did memory address calculationsrcxwas the count register which held a loop counterrdxwas the data register which you could use for I/O port accessrdiwas the destination index register which pointed to the “destination” of a string operationrsiwas the source index register which pointed to the “source” of a string operationrbpwas the base pointer which pointed to the base of the current stack frame.rspwas the stack pointer.Source - StackOverflow

Other than rsp (used for stack pointer) and rbp (used for base pointer), other registers are used as general purpose now and not actually used

for what they were original purposes. There are 8 more generate purpose registers from r8 - r15.

x86-64 Instruction Format

<opcode> <operand-list>.

Here,

<opcode>is a short mnemonic indetifying the type of instruction<operand-list>is a 0, 1, 2 or (rarely) 3 operands seperated by commas.- Typically all the operands are sources while one can be the destination as well.

Example: addl %edi, %ecx ; Here %ecx is both the source and destination, like %edx = %edx + %edi

There are 2 types of syntax.

- AT&T Syntax

- Generated by clang, objecdump, perf

- Last operand is the destination

<op> A, BmeansB <- B <op> A

- Intel Syntax

- Used in Intel manuals

- First operand is the destination

<op> A, BmeansA <- A <op> B

Opcode Suffixes

- Suffixes can be added to the opcodes to describe the data type of the operation or a condition code.

- A single character suffix is used.

- If none provided, inferred from the sizes of the operand registers.

Example: movq -16(%rbp), %rax ; Moves a 64 bit integer as quad means 4 16-bit words

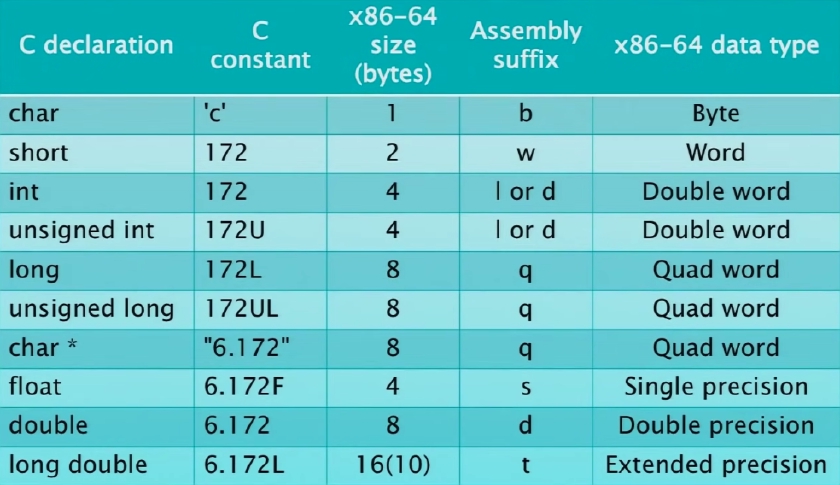

x86-64 Data Types

- Sign-extension or zero-extension opcodes use two data-type suffixes.

movzbl %bl, %edx- Move value from 8bit%blregister to 32bit%edxregister with zero being filled in higher bits.movslq %eax, %rdx- Move value from 32bit%eaxto 64bit%rdxwith sign bit being filled in higher bits (eg.1011 => 11111011and0011 => 00000011).

- Results of 32 bit ops are implicitly zero-extended to 64 bits values. This does not happen for 8 or 16 bit ops (hence garbage in higher bits if not specified).

Conditional Operations

Conditional jumps and conditional moves use a one or two character suffix to indicate teh condition code.

Example:

cmpq $4096, %r14 ; Set a flag in a RFLAG register

jne .LBB1_1 ; Jump if value in reg 14 != 4096

RFLAGS Registers

- Bits(0), Abbr(CF), Desc(Carry) - Last ALU op generated a carry

- Bits(1), Reserved

- Bits(2), Abbr(PF), Desc(Parity) - 0 if result of last op had odd 1 bits, 1 otherwise

- Bits(3), Reserved

- Bits(4), Abbr(AF), Desc(Adjust) - NA

- Bits(5), Reserved

- Bits(6), Abbr(ZF), Desc(Zero) - Result of last ALU op was 0

- Bits(7), Abbr(SF), Desc(Sign) - Last ALU op produced a value whose sign bit was set

- Bits(8), Abbr(TF), Desc(Trap) - If set to 1, processor will execute instructions one-by-one (imagine debugger)

- Bits(9), Abbr(IF), Desc(Interrupt enable) - Refer wiki

- Bits(10), Abbr(DF), Desc(Direction) - Refer wiki

- Bits(11), Abbr(OF), Desc(Overflow) - Last ALU caused overflow

- Bits(12..=63), System Flags or Reserved

Condition Codes

- Code(a), RFLAGS(CF = 0, ZF = 0), Desc(if above)

- Code(ae), RFLAGS(CF = 0), Desc(if above or equal)

- Code(c), RFLAGS(CF = 1), Desc(on carry)

- Code(e), RFLAGS(ZF = 1), Desc(if equal)

- Code(ge), RFLAGS(SF = OF), Desc(if greater or equal)

- Code(ne), RFLAGS(ZF = 0), Desc(if not equal)

- Code(o), RFLAGS(OF = 0), Desc(on overflow)

- Code(z), RFLAGS(ZF = 1), Desc(if zero)

NOTE: Processor uses substraction for comparisons.

x86-64 Direct Addressing Modes

- The operands of an instruction specify values using a variety of addressing modes.

- At most one operand may specify a memory address.

I think, this means that we cannot do something like

movq 0x172 0x180.

Direct Addressing Modes

- Immediate: Use the specified value. Eg.

movq $172, %rdi. - Register: Use the value in the specified register. Eg.

movq %rcx, %rdi - Direct memory: Use teh value at the specified addres. Eg.

movq 0x172, %rdi

x86-64 Indirect Addressing Modes

- Indirect === Allow specifying memory address by some computation.

Indirect Addressing Modes

- Register indirect: The address is stored in the specified register. Eg.

movq (%rax), %rdi - Register indexed: The address is a constant offset of the value in the specified register. Eg.

movq 172(%rax), %rdi - Instruction-pointer relative: The address is indexed relative to

%rip. Eg.movq 172(%rip), %rdiHow is this different from Register indexed?

- Base Indexed Scale Displacement: This mode refers to the address

Base + Index*Scale + Displacement.- Eg.

movq 172(%rdi, %rdx, 8), %raxwhere%rdiis base,8is scale,%rdxis index and172is the displacement. - Displacement can be any 8, 16 or 32 bit value.

- Scale can be either 1, 2, 4, or 8.

- Base and Index need to be a GPR.

- If unspecified, Index and Displacement default to 0.

- If unspecified, Scale default to 1.

- Use very frequently to access stack data, we have access to the frame base and it can be used to access data in the frame.

- Eg.

Jump Instructions

jmpandj<condition>take a label as their operand which identifies a location in the code.- Labels can be symbols, exact addresses or relative addresses.

- An indirect jump takes an indirect address as its operand. Example

jmp *%eax.

Example 1:

jge LBB0_1

...

LBB0_1:

leaq -1(%rbx), %rdi

Example 2:

jge 5 <_fib+0x15> ; I have no idea what the fuck this does.

...

15:

leaq -1(%rbx), %rdi

Interesting Assembly Idioms

xor %rax %rax- Zeroes the register. Maybe quicker thanmov $0 %rax?test A, Bcomputes teh bitwise AND ofAandBand discard the result, preserving the RFLAGS.- There are several no-op instructions like

nop,nop Aanddata16.- They will do nothing.

- However, they will set RFLAGS.

- A compiler may generate these to improve memory alignment such that the instruction is aligned with the cache line (there is C directive for this as well).

Floating-Point and Vector Hardware

- Previously FP ops were done on the software side.

- SSE and AVX do single and double precision scalar FP arithmatic.

- x87 (from 8087) support single (

float), double (double) and extended precission (double float) scalar FP arithmatic. - SSE and AVX instruction sets also include vector instructions.

- Compilers prefer to use SSE instructions over x87 instructions as they are simpler to compile for and to optimize.

SSE opcodes are similar to x86 opcodes

movsd (%rcx, %rsi, 8), %xmm1 mulsd %xmm0, %xmm1 addsd (%rax, %rsi, 8), %xmm1 movsd %xmm1, (%rax, %rsi, 8)

- SSE instructions use 2 letter suffixes to encode the data type

ss-floatsd-doubleps- vector of single precisionpd- vector of double precision- Here

- First

sstands for single - First

pstands for packed - Second

sstands for single-precision - Second

dstands for double-precision

- First

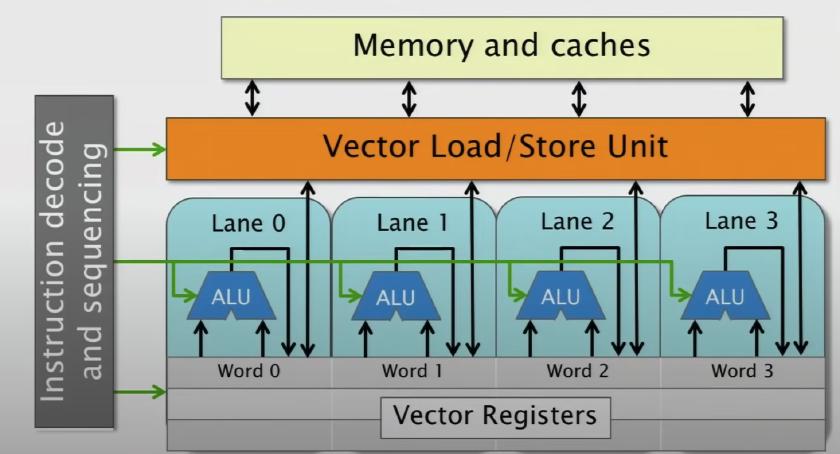

Vector Hardware

- Performs same action on a large register (that is broken down into smaller words). They all operate in a lock step.

- Depending on the architecture, memory might need to be aligned. Usually there is a performance difference, always align.

- Some machines might support per lane operations as well.

- There is support for multiple vector-instruction sets

- SSE instruction set - Support integer, floats and doubles.

- AVX instruction set - Support floats and double.

- AVX2 instruction set - Support interger, floats and doubles.

- AVX-512 (AVX3) instruction set - Register length increased to 512 bits and added new vector operations (including popcount).

SSE vs AVX and AVX2

- Mostly AVX and AVX2 extend the SSE instruction set.

- SSE instruction use 128bit XMM vector registers and operate on at most 2 operands at a time.

- AVX instructions can alternatively use 256bit YMM vecotr registers and can operator on 3 operands at a time: 2 source and 1 destination

operand.

Example:

; This will add values in register ymm0 and ymm1 and will store it in ymm2 vaddpd %ymm0, %ymm1, %ymm2 ; %ymm2 is the destination operand - YMM registers alias XMM registers so mutating

%xmm0will change the value for%ymm0.

Computer Architecture

Each instruction is executed through 5 stages (Vastly simplified):

- Instruction Fetch (IF) - Read from memory.

- Instruction Decode (ID) - Determine units and extract register args.

- Execute (EX) - Perform ALU operations.

- Memory (MA) - R/W data memory.

- Write back (WB) - Store result into registers.

The 5 stage over-simplified processor does not talk about:

- Vectors - Already discussed above.

- Super scalar processing

- Out of order execution

- Branch prediction

Pipelined Instruction Execution

- Processor hardware exploits instruction-level parallelism by finding opportunities to execute multiple instructions simultaneously in different pipeline stages.

- Pipelining will not improve latency but will improve throughput as we can have many instructions in the pipeline.

- In practice it isn’t always feasible due to pipeline stalling. Pipeline stalling can happen due to hazards. There are 3 types of hazards:

- Structural hazard: Two instructions attempt to use the same functional unit at the same time.

- Data hazard: An instruction depends on the result of a prior instruction in the pipeline.

- True Dependence: Read After Write

- Anti Dependence: Write After Read

- Output Dependence: Write After Write

- Control hazard: Fetching and decoding the next instruction to execute is delayed by a decision about control flow (ie. a conditional jump).

- For complex pipelining, the idea is to have different functional units which do different things such that slower functional units do not affect faster ones (for eg. FP ops are slow mostly).

- Bypassing - Allows an instruction to read its arguments before they have been stored in a GPR.

- Out of Order Execution - There are a bunch of tricks that the hardware can employ to eliminate dependence among the instructions which allow the processor to execute the instructions out of order. More details in the video.

- Branch Prediction - In case the processor encounters a conditional, it is going to do speculative execution where it basically guesses the outcome and will execute the branch.

C to Assembly

Tip:

GOOS=<os> GOARCH=<arch> go tool objdump -S <binary>will show assembly for that platform regardless of the host 🤯!!

LLVM IR

LLVM IR - LLVM Intermediate Representation. C compiler (clang) would compile C code into LLVM IR.

To compile to LLVM IR run clang -S -emit-llvm <c-file>

Vs Assembly

- LLVM IR is similar to assembly

- LLVM IR instruction format

<destination operand> = <opcode> <source operands>. - Control flow is implemented using conditional and unconditional branches, no implicit FLAGS register or condition codes.

- LLVM IR has smaller instruction set.

- LLVM IR can have infinite registers!!

- No explicit stack pointer or base pointer.

- C like type system.

- C like functions.

LLVM IR example for a fib calculation program

; fib.ll

define i64 @fib(i64) local_unnamed_addr #0 {

%2 = icmp slt i64 %0, 2

br i1 %2, label %9, label %3

; <label>:3: ; preds = %1

%4 = add nsw i64 %0, -1

%5 = tail call i64 @fib(i64 %4)

%6 = add nsw i64 %0, -2

%7 = tail call i64 @fib(i64 %6)

%8 = add nsw i64 %7, %5

ret i64, %8

; <label>:9: ; preds = %1

ret i64 %0

}

Registers

- LLVM IR stores values variables called registers.

- Syntax:

%<name> - Function scoped.

- Caveat: LLVM hijacks its syntax for registers to refer to “basic blocks”.

Instructions

- Syntax for instructions that produce a value:

%<name> = <opcode> <operand list>. - Syntax for instructions that do not produce value:

<opcode> <operand list>. - Operands are registers, constants or even “basic blocks”.

- Arguments are evaluated before operations and intermediate results are saved in registers.

Data Types

- Integers:

i<number>- Just like zig (or zig is like LLVM IR) - FP values:

double,float - Arrays:

[<number> x <type>] - Structs:

{ <type>, ... } - Vectors: <

x > - Pointers:

* - Labels (aka Basic Blocks):

label - Aggregate types like struct/array are typically stored in memory hence access involves first calculating the address and then loading the data.

- Address calculation is done by

getelementptrinstruction from a pointer and a list of indices.; computes the address %2 + 0 + %4 ; [7 x i32]* is the pointer into memory and adds indices literal value and 0 and value stored ; in register %4 %5 = getelementptr inbounds [7 x i32], [7 x i32]* %2, i64 0, i64 %4

- Address calculation is done by

Functions

- Most often, every C function will have a equivalent in the LLVM IR.

- Function definition and declaration and similar to C.

retstatement acts like C’sreturn.local_unnamed_addrmeans that the function parameters are automatically named%0,%1,%2, etc.

Basic Blocks

- The body of a function is partioned into basic blocks: sequences of instructions where control only enters through the first instruction and only exits from the last.

Conditionals

bris the conditional branch instruction. Syntaxbr <predicate>, <block-if-true>, <block-if-false>.- It is possible to have an unconditional branch in LLVM IR. In this case the syntax is:

br <block>. Eg.br label %6.

Loops

- LLVM IR representation maintains the static single assignment (SSA) invariant: a register is defined by at most one instruction in a function.

- This poses the problem for implementing loops like what happens when control flow merges, eg. at the entry point of a loop?

- Loops can be simply implemented by

brinstructions as it allows to jump to any label. However, C loops are a bit more nuanced than that. Cforloops have initialization, condition check, and updation of induction variable. This structure poses a problem as SSA would not allow updating the register value and the at the same time we do need a mechanism to track the value of our “induction” variable.- This problem is solved by the

phiinstruction.phiinstruction simply lists that what the value should be considering from which block the control flow has entered. Syntaxphi <type> [ <value> <block> ] [ <value> <block> ] ....

- This problem is solved by the

LLVM IR Attributes

- LLVM IR constructs (eg instructions, operands, functions and function parameters) might be decorated with attributes.

- Some come directly from the source code while some come from compiler analysis.

Translating LLVM IR to Assembly

- The compiler must perform three tasks to translate LLVM IR into x86-64 assembly

- Select assembly instructions to implement instructions.

- Allocate GPA registers to hold values.

- Coordinate function calls.

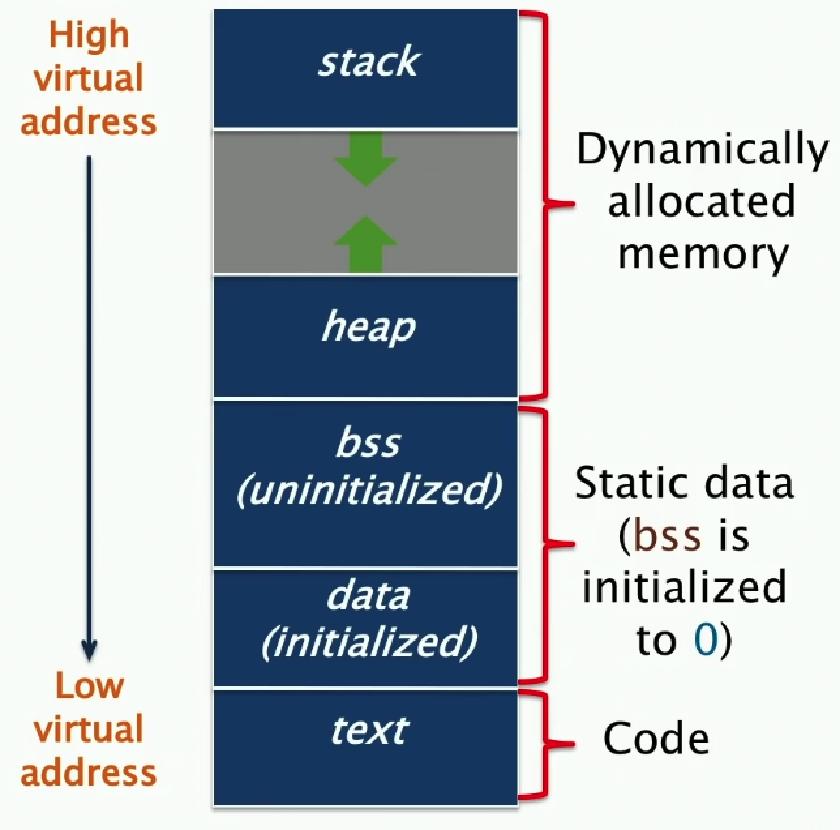

Layout of a Program in Memory

Assembler Directives

- Assembly code contains directives that refer to and operate on sections of assembly.

- Segment directives

- Organize the contents of the assembly file into segments.

.text- for text segment.bss- for bss segment.data- for data segment

- Storage directives

- Store content into current segment

- Examples:

x: .space 20 ; allocate 20 bytes at location xy: .long 172 ; store the const 172L at location y

🤔: I don’t understand how would I refer to these data in the assembly?

- Scope and linkage directives

- Controls linking

- Example:

.globl fib ; make fib visible to other object files.

The Call Stack

- Stores data in memory to manage function calls and returns.

- Stores

- Return address of a function call.

- Register state so different functions can use the same registers.

- Function arguments and local variables that don’t fit in registers.

This Linux x86-64 Calling Convention

- It organizes the stack into frames, where each function instantiation gets a single frame of its own.

- The

%rbpregister points to the top of the current stack frame. - The

%rspregister points to the bottom of the current stack frame. - The

callinstruction in x86-64 pushes the%riponto the stack and jumps to the operand, which is the address of a function. - The

retinstruction in x86-64 pops%ripfrom the stack and returns to the caller. - In case of function execution, it is possible that the callee function and caller function want to use the same registers. This problem requires that

somehow the values in the registers should be stored in the memory either by callee, by caller or by both.

- Linux x86-64 calling convention goes with the last solution.

- Callee-saved registers:

%rbx,%rbp,%r12-%r15 - All other registers are caller-saved.

- Walkthrough is here. Worth checking out at least once. For more info, need to look at System V ABI.

Compilers love using leaq for simple arithmatic because they can have a different destination register unlike what they get in with the simple

add instruction.

Multicore Programming

- If a processor wants to read a value

x, it will load it from memory, save it into its cache and then will load that to one of its registers. - Other processors can either read from the main memory or can be read from another processor’s cache.

Not sure why this isn’t the default though?

- Multicore hardware need to solve the problem of cache coherence. They use a protocol like MSI protocol for doing so.

- Done at the granularity of the cache line instead of per item.

M: cache bock has been modified. No other caches contain this block inMorSstates.S: other caches maybe sharing this block.I: cache block is invalid (treated as not being there)

- Before a cache modifies a location, the hardware first invalidates all other copies.

- It was raised in the lecture that if processors are going to communicate that the cache is invalid why not instead communicate the update value? In some complex protocols, they do.

- When the processor needs to access the value, it needs to ensure that the value is not in

Istate, if it is then it needs to fetch (either form main memory or from cache of another processor) the fresh value. - There are many protocols like

MESI, etc. - When a bunch of processors try to update the same value then that can lead to invalidation storm which can become a huge performance bottlenecks.

- Done at the granularity of the cache line instead of per item.

Concurrency Platforms

- Abstracts processor cores, handles synchronization and communication protocols and performs load balancing.

Pthreads

- Standard API for threading specified by ANSI/IEEE POSIX 1003.1-2008.

- Built as a library.

- Each threads implements an abstraction of a processor, which are multiplexed onto machine resources.

- Threads communicate through shared memory.

- Library functions mask the protocols involved in interthread coordination.

- Example functions

int pthreate_create(pthread_t *thread, const pthread_attr_t *attr, void *(*func)(void *), void *arg)int pthread_join(pthread_t thread, void **status)

- Issues

- Overhead: The cost of creating a thread more than \(10^4\) cycles => coarse-grained concurrency. Here thread pools might be helpful.

- Scalability: Harder to scale.

- Code Simplicity: Marshalling and unmarshalling of arguments could error prone but is left to the consumers of the library.

Intel Threading Building Blocks

- C++ library on top of pthreads.

- Offers an abstraction of task.

- Uses work-stealing algorithm to load balance tasks across threads.

- Focus on performance.

- Example: Not worth it, looks just another concurrency library.

OpenMP

- Unlike Intel TBB and pthread which are library solutions, OpenMP is a linguistic solution.

- Linguistic extensions to C/C++ and Fortran in the form of compiler pragmas.

- Supported by GCC, ICC, Clang and Visual Studio.

- Runs on top of native threads.

- Supports loop parallelism, task parallelism and pipeline parallelism.

- Provides many pragma directives to express common patterns such as

parallel forfor loop parallelismreductionfor data aggregation- directives for scheduling and data sharing

- Also supplies sync primitives like barriers, atomics, mutex, etc.

- Example (performs better than TBB alternative)

int64_t fib(int64_t n) { if (n < 2) return n; int64_t x, y; #pragma omp task shared(x, n) x = fib(n - 1); #pragma omp task shared(y, n) y = fib(n - 2); #pragma omp taskwait return (x + y); }

What’s the catch?

Intel Cilk Plus

- The “Cilk” part is a small set of linguistic extensions to C/C++ to support fork-join parallelism.

- The “Plus” part supports vector parallelism.

- Features a provably efficient work-stealing scheduler.

- Provides a hyperobject library for parallelizing code with global variables.

- Ecosystem has

- Cilkscreen for race detection

- Cilkview for scalability analysis

- Example

int64_t fib(int64_t n) { if (n < 2) return n; int64_t x, y; x = cilk_spawn fib(n - 1); y = fib(n - 2); cilk_sync; return (x + y); }

What’s the catch? Maybe using a custom compiler is the catch.

Races and Parallelism

- Determinancy Race: Occurs when two logically parallel instructions access the same memory location and at least one of the instructions performs a write.

- Two sections of code are indepedent if they have no determinancy races between them.

- Avoiding Races in Cilk

- Iterations of a

cilk_forshould be independent. - Between a

cilk_spawnand the correspondingcilk_sync, the code of the spawned child should be independent of the code executed by additional spawned or called children. - Machine word size matters. Watch out for races in packed data structures.

Example:

// Updating x.a and x.b in parallel may cause a race. // Depends on compiler optimization level // Safe on intel x86-64 // --! Someone mentioned that C11 mandates that this should be safe !-- struct { char a; char b; } x; - Use cilksan race detector.

- Iterations of a

- Parallelism

- A parallel instructions stream is a DAG

G = (V, E) - Each vertex \(v \in V\) is strand: a sequence of instructions not containing a spawn, sync or return from a spawn.

- First instruction is called initial strand, last instruction is called the final strand.

- A strand is called ready if all its predecessors have executed.

- An edge \(e \in E\) is a spawn, call, return or continue edge.

- spawn edge corresponds to a function that was spawned.

- call edge corresponds to a function that is called.

- return edge corresponds to a return back to the caller of the function.

- continue edge corresponds a function execution after the spawn call.

- Cilk

- Computation DAG is processor oblivious.

cilk_foris converted to spawns and syncs using recursive divide-and-conquer.

- Amdahl’s “Law”

- If 50% of your application is parallel and 50% is serial, you can;t get more than a factor of 2 speedup, no matter how many processors it runs on.

- In general, if a fraction \(\alpha\) of an application must be run serially, the speedup can be at most \(1/\alpha\).

- Gives a very lose upper bound, not very useful.

- Performance Measures

- \(T_p\) is execution time on P processors.

- \(T_1\) is work.

- \(T_{\infty}\) is span, also called critical-path length or computatational depth. It also called the same because

it is the time required if we had inifinite number of processors.

- It is so because no matter how many processors we have, we are limited by the maximum number of sequential ops that need to be performed.

- Work Law: \(T_p \geq T_1 / p\).

- Span Law: \(T_p \geq T_{\infty}\).

- Series Composition

- Work: \(T_1\left(A \cup B\right) = T_1\left(A\right) + T_1\left(B\right) \).

- Span: \(T_{\infty}\left(A \cup B\right) = T_{\infty}\left(A\right) + T_{\infty}\left(B\right) \).

- Parallel Composition

- Work: \(T_1\left(A \cup B\right) = T_1\left(A\right) + T_1\left(B\right) \).

- Span: \(T_{\infty}\left(A \cup B\right) = \max \left \{T_{\infty}\left(A\right), T_{\infty}\left(B\right) \right\} \).

- Speedup: \(T_1 / T_p\) is speedup on \(P\) processors.

If \(T_1 / T_p \lt P\), we have sublinear speedup.

If \(T_1 / T_p = P\), we have (perfect) linear speedup.

If \(T_1 / T_p\), we have superlinear speedup, which is not possible in this simple performance model, because of the work law.

In practice this might happen sometimes due to higher cache availability.

- Parallelism: \(T_1 / T_{\infty}\)

- This is the average amount of work per step along the span.

- CilkScale can draw these plots.

- A parallel instructions stream is a DAG

- Scheduling Theory

- Greedy Scheduling: Do as much as possible on every step.

- There are 2 kinds of steps in a greedy scheduler

- Complete Step

- \(\ge P\) strands ready.

- Will run any \(P\).

- Incomplete Step

- \(\lt P\) strands ready.

- Will run all \(P\).

- Complete Step

- Analysis:

- Any greedy scheduler achieves \(T_p \le T_1 / P + T_{\infty}\)

- Any greedy scheduler achieves within a factor of 2 of optimal.

- Any greedy scheduler achieves a near-perfect linear speedup whenever \(T_1 / T_{\infty} \gg P \).

Analysis of Multithreaded Algorithms

- Master Theorem: \(T(n) = aT(n / b) + f(n)\) where \(a \ge 1\) and \(b \gt 1\).

- Case 1: \(f(n) = O(n^{\log_b a - \epsilon})\), constant \(\epsilon \gt 0\) \(\implies T(n) = \Theta(n^{\log_b a})\).

- Case 2: \(f(n) = O(n^{\log_b a} \lg^k n)\), constant \(k \ge 0\) \(\implies T(n) = \Theta(n^{\log_b a} \lg^{k + 1} n)\).

- Case 3: \(f(n) = \Omega(n^{\log_b a + \epsilon})\), constant \(\epsilon \gt 0\) (and regularity condition) \(\implies T(n) = \Theta(f(n))\).

- Loop Parallelism in Cilk:

- Implementation example

cilk_for (int i = 1; i < n; ++i) { for (int j = 0; j < i; ++j) { double temp = A[i][j]; A[i][j] = A[j][i]; A[j][i] = temp; } } // The above gets converted to void recur(int lo, int hi) { if (hi > lo + 1) { int mid = lo + (hi - lo) / 2; cilk_spawn recur(lo, mid); recur(mid, hi); cilk_sync; return; } int i = lo; // This loop is copied directly for (int j = 0; j < i; ++j) { double temp = A[i][j]; A[i][j] = A[j][i]; A[j][i] = temp; } } // ... recur(1, n);- Work: \(T_1(n) = \Theta(n^2)\)

- Span: \(T_{\infty}(n) = \Theta(\lg n + n) = \Theta(n)\) Parallelism: \(T_1(n)/T_{\infty} = \Theta(n)\)

- Analysis of Nested Parallel Loops (extension of above)

cilk_for (int i = 1; i < n; ++i) { cilk_for (int j = 0; j < i; ++j) { double temp = A[i][j]; A[i][j] = A[j][i]; A[j][i] = temp; } }- Work: \(T_1(n) = \Theta(n^2)\)

- Span: \(T_{\infty}(n) = \Theta(\lg n)\)

- Span of outer loop control is \(\Theta(\lg n)\)

- Span of inner loops control is \(\Theta(\lg n)\)

- Span of body is \(\Theta(1)\). It is 1 because now there is no iteration, the iterations are replaced with the spawns which are accounted for in the inner loops control above.

- Parallelism: \(T_1(n)/T_{\infty} = \Theta(n^2/\lg n)\)

- This seems like a better algorithm than the above but in reality it might not be. We just have to ensure that the parallelism is more than the number of cores we have access to. \(\Theta n\) is already large in comparison to the processors we usually have access to, hence further parallelism would not add any benefit but would add the overhead of parallelism.

- Work that we accounted for above, includes substantial overhead. This can be improved by coarsening the parallelism

- Example. Let \(G\) be the grain size, \(I\) be the time for one iteration of the loop body and \(S\)

be the time to perform a spawn and return.

#pragma cilk grainsize G cilk_for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) A[i] += B[i]; // The above gets converted to the following void recur(int lo, int hi) { if (hi > lo + G) { int mid = lo + (hi - lo) / 2; cilk_spawn recur(lo, mid); recur(mid, hi); cilk_sync; return; } for (int i = lo; i < hi; ++i) A[i] += B[i]; } // ... recur(0, n);- Work: \(T_1 = n.I + (n / G - 1).S \).

- Span: \(T_{\infty} = G.I + \lg(n / G).S\).

- To minimize overhead, we need to make sure \(G \gg S / I\) and \(G\) is small.

- Example. Let \(G\) be the grain size, \(I\) be the time for one iteration of the loop body and \(S\)

be the time to perform a spawn and return.

- Implementation example

- Performance Tips

- Minimize the span to maximize parallelism. Try to generate 10 times more parallelism than processors for near-perfect linear speedup.

- If you have plenty of parallelism, try to trade some of it off to reduce overhead.

- Use divide-and-conquer recursion or parallel loops rather than spawning one small thing after another.

- Ensure that work/len(spawn) is sufficiently large.

- Coarsen by using function calls and inlining near the leaves of recursion rather than spawning.

- Parallelize outer loops as opposed to inner loops, if you are forced to make a choice.

- Watch out for scheduling overhead.

What compilers can and cannot do?

- Simple model of compiler

- Performs a sequence of transformation passes on the code

LLVM IR -> Transform -> Transform -> ... -> Optimized LLVM IR- Each pass analyzes and edits the code to try to optimize the code’s performance.

- A transformation pass might run multiple times.

- Passes run in a predetermined order that seems to work well most of the time.

- Performs a sequence of transformation passes on the code

- Clang/LLVM can produce reports for many of its core transformation passes

Rpass=<string>produces reports of which optimizations matching<string>were successful.Rpass-missed=<string>produces reports of which optimizations matching<string>were not successful.Rpass-analysis=<string>produces reports of the analyses performed by optimizations matching<string>.- The argument

<string>is Regex. To match with anything, use.*. - Not all transformation passes generate reports.

- Reports don’t always tell the whole story.

- Compiler Optimizations

- Based on New Bentley’s rules

- Loops

- Hoisting

- Loop unrolling

- Loop Fusion (kinda)

- Eliminating wasted iterations (kinda)

- Logic

- Constant folding and propagation

- Common-subexpression elimination

- Algebraic identities

- Short-circuiting

- Ordering tests (kinda)

- Combining tests (kinda)

- Functions

- Inlining

- Tail-recursion elimination

- Loops

- More compiler optimizations (beyond bentley)

- Data Structures

- Register allocation

- Memory to registers

- Scalar replacement of aggregates

- Alignment

- Loops

- Vectorization

- Unswitching

- Idiom replacement

- Loop fission

- Loop skewing

- Loop tiling

- Loop interchange

- Logic

- Elimation of redundant instructions

- Strength reductions

- Dead-code elimination

- Idiom replacement

- Branch reordering

- Global value numbering

- Functions

- Unswitching

- Argument elimination

- Data Structures

- This is a moving target, new optimizations are continuously added to the compilers.

- Most compiler optimizations happen on the compiler’s IR although not all of them. It was demonstrated how compilers can perform further optimizations during IR to assembly translation (like avoiding multiplication and division operations by whatever means possible).

- If a function is in different compilation unit it usually cannot be inlined. This can be done using link-time optimization (LTO).

static inlineis only a hint to the compiler.- Memory aliasing makes a compiler very conservative.

- Use

restrictandconstkeywords wherever possible.

- Use

- Based on New Bentley’s rules

- Cannot do:

- Compiler knows business logic so sometimes the obvious optimizations will be missed by the compiler just because the compiler is unaware of the business logic.